Who has seen my Instagram? (It is right hereeeeeee SHAMELESS PLUGGGGG)

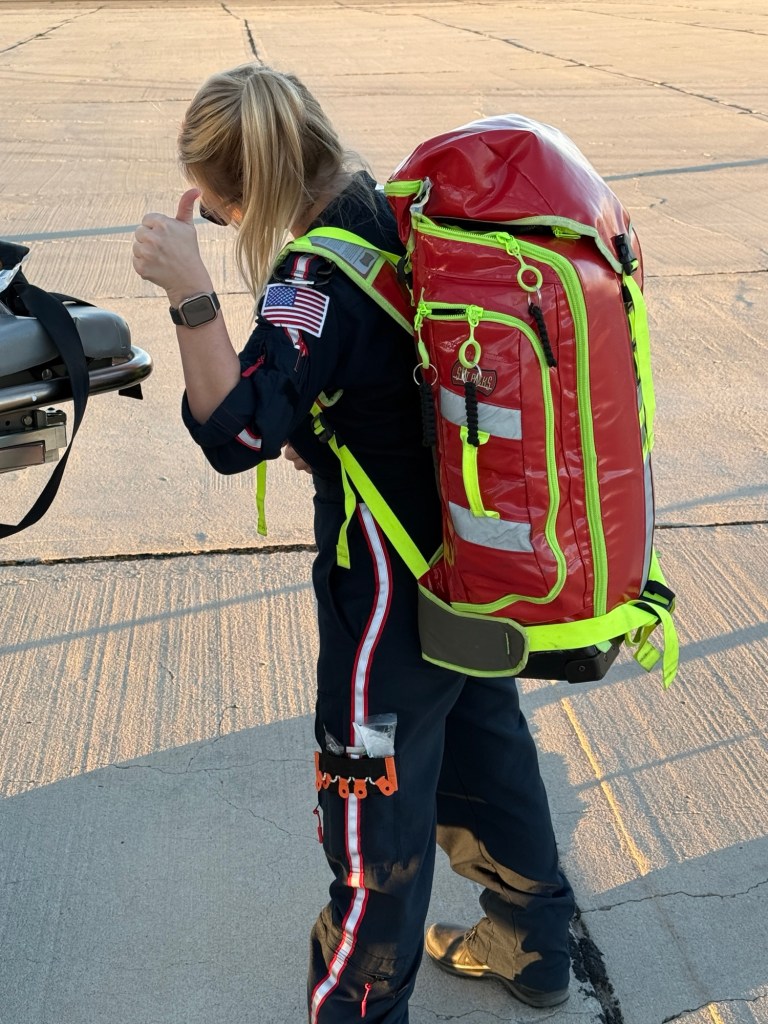

From the outside looking in, my life looks pretty damn charmed. Right?! Solid marriage with a great husband, cute dogs (and I guess an ok cat), beautiful home, amazing/successful career, world traveler, up and coming social media savant (as I’ve been told), and getting my fitness into shape after a life of feeling like an ugly duckling.

Social media has a way of allowing us to create the picturesque dreamscape of a life–complete with vibrant filters and floating hearts as our followers flick their thumbs over the images in the “like” gesture as they move on to the next glamour shot. People sit in the quiet of their living rooms, pondering how mediocre their own lives, spouses, or careers are in comparison to these online personalities of their friends’ or families’ or favorite influencers’ and wonder how they went so wrong. But they forget that the internet is a series of smoke and mirrors; often the whole truth is veiled behind thin half truths or outright lies.

Too often, we lack the entire story. We miss out on the means and simply see the ends.

As a result, our own triumphs seem shadowed by those of others because we see only their “good things” and never the bad. However, it’s really the survival of the bad that defines who are when we get to our “good thing.”

So I’m here to tell you this. No person, no matter how picture perfect they may seem is perfect and honestly, I’d rather the person who has been through hell and back over the person who has never struggled a day in their life to take care of me. Give me the single parent, the child of drug addicted parents or even the survivor of drug addiction, the veteran who has seen war and death, the medical student who struggled through school because of finances, the nursing student who might’ve failed out once before getting his life straight… I want the person who has known what is like to have failed.

I am positive many of my readers have heard the analogy about broken bones… well we know that there is a modicum of truth to the saying. After a bone is broken, the area the bone is broken grows back stronger. Now, we won’t debate the actual physiology in this statement but we’ll use it for this illusion.

When you go through hardship, one of two things can happen…

- You succumb to the failure.

- You accept it, learn from it, grow from it, move forward.

So when the bone breaks, you can either reset it and allow it to heal and grow back stronger or you can leave it mangled and useless. The choice is yours.

People who choose to heal are those people I prefer as my colleagues because they have a great deal of traits consistent with emotional resiliency. These people are forged in fire. Like steel, they are strengthened by the flames.

What is resiliency, though? It is the rubber band of our constitution. It is our capability to bounce back. By definition, it is our ability to mentally or emotionally cope with a crisis or return to our pre-crisis state quickly. It is our ability to mitigate the negative effects of external stressors on our internal psyche. For some, this may be a native skill while others had to adapt over time when exposed to crisis. Further, it is important to note, the definition of crisis isn’t static–crisis to one person can be an entirely different meaning to another. It simply means that it creates great potential for suffering for an individual and because of the dynamic natural of humanity, the spectrum of what constitutes a crisis is broad. What matters, is how does the crisis affect a person and how to they cope with it. Overcoming the crisis dictates their resilience.

Think of a time you had a problem. One that caused you great emotional turmoil. How did it make you feel? I’m sure the first thing you felt was your heart rate go up. You could feel the flutter in your chest. Maybe your stomach felt strange. A sweat on the back of your neck. Your respirations may have increased. Stereotypical fight or flight mode. The surge of the epinephrine as the sympathetic nervous system activated. Your brain racing.

And then as the crisis settled, the tiredness. The concerns. The replaying of the scenario. The planning. The promises to yourself. The criticism of your actions. The blaming of yourself or others. The regrets. Maybe instead the pride in your work or your team mates. Or maybe simply…nothing at all.

More time passed. The feelings abated. Each feeling you went through felt a little less intense. You remembered the take-aways but the FEELINGS associated with the event were less sharp.

Resilience. You got through it. You survived whatever that thing was.

What Do I Know About Survival?: A Series of Unfortunate Events

For me, it was a series of years where I wanted to quit. My childhood wasn’t necessarily hard but at times it wasn’t easy. My parents loved me, there was no question about that but at times it did not always seem like they were ready for me. My father struggled with his own demons throughout my life while my mom, still young and developing her own career, had me unexpectedly. Their relationship was tumultuous at times given the circumstances but ultimately, they seemed to figure it all out. They saw the best in people, despite their sometimes questionable backgrounds–it is a trait I carry on myself, one that sometimes gets me burned in the end.

As a teenager, I was sexually assaulted over the course of a few year relationship and struggled heavily with my own issues with depression and anxiety. I fought constantly with my parents, as teenagers do. It is a joke I like to make that I was often grounded more than I wasn’t simply because I bucked against my dad a lot. Even in my teenage years though, I had a great work ethic often working at minimum 2 jobs from the time I was 15, sometimes 3 or 4 depending if a previous employer needed under the table work or a babysitter.

Towards my later teenage years, I went through a devastating breakup with the first real love of my life and needed something to take my mind off that. So I decided to enroll in EMT class. I had an interest in medicine and figured it would be a great way to start off a career. Well… I didn’t focus and failed about a handful of weeks in. I was humiliated. I asked the instructor to audit the course for the rest of the semester despite the fact I wouldn’t be able to test with my class mates and although it wasn’t typical, he allowed me to. I re-enrolled the next semester and had one of the highest cumulative averages. And this was the entire foundation for my flight career later in life.

Getting to college, I thought I was in for a fresh start. I got to Philadelphia to a fancy (and expensive) private Catholic university where I was starting as a pre-med major with 20+ credits my first semester. I was excited to pledge a sorority, play rugby, and make new friends. But soon that changed. My boyfriend back home guilted me about going away to school “for a piece of paper”. My friends got me into heavy drinking and drugs. My depression started to rear its ugly head again until I completely stopped leaving my room, going to class, and even eating. None of my professors even noticed my absence. It wasn’t until my suicide note was discovered the day I had planned to hang myself in my dorm room that I was noticed. It was almost 2 weeks I had been missing from classes.

I was taken to the Dean’s office by security. I was delirious from not eating or drinking for days, messy from not showering for days. I was being grilled questions I couldn’t answer. I just wanted to sleep. I was driven to a hospital and taken into an emergency room where there were white walls, lots of windows into patient rooms, and patients were yelling. I was put into a room with only a bed, bolted to the floor. A physician’s assistant came in to speak with me–when I asked for my mom, she ignored me and asked me about my period. When I told her I didn’t know when my last one was (because I had no idea what day it was and because my birth control was messed up), my response was “you’re 18, how do you not know when your last period was? Stop being obtuse!” And she walked out.

It was cold, I wasn’t given a blanket. The older man in the room next to me kept staring at me through the glass. I was alone. I was being involuntarily committed to a psychiatric facility but luckily I was given the option to voluntarily ask for help, which I did. I spent over a week getting treatment and while I never would want to do it again, it saved my life, and I am so thankful it did.

I returned to school in the spring with another 20 credits but all in all, my freshman year of college, of the 40+ credits I took, I passed 4 of them. It was a humiliating and expensive experience. But it was a lesson. It was a growing pain. A broken bone.

The next school year, I transferred to a technical college in Central Pennsylvania and lived at a firehouse. In exchange for running ambulance calls at night, I received free room and board. I ditched the unsupportive, going nowhere boyfriend and met my now husband. I started coursework in a paramedic program and my grades were getting better. Not quite great yet, but I passed everything. I was much happier. I changed majors again to nursing the next year.

Then in 2010, the night before a major anatomy and physiology exam, I wrecked my car. I had just dropped my boyfriend off to pick up his vehicle at the mechanic and was driving home on the highway. We had finished a fire company meeting; I was tired and wanted to get to sleep for my exam in the morning. I will never know the events leading up to the crash because I had lost the memories of days prior to the event, but my car went off the roadway, rolled 6-7 times, and came to a rest down a steep embankment on its roof. From the highway, the car was completely invisible.

My boyfriend had made it home and saw I wasn’t home yet despite leaving a few minutes before him. He received a phone call from me, my voice panicked stating “I don’t know where I am and there is blood in my ear.” Of course, I didn’t call 9-1-1, I called him. He told me to hang up and call 9-1-1. He called 9-1-1 to tell them where he thought I could be and I also called. Units went up and down the highway looking for me for a while. I was found by a fire police unit as I was walking down the road, bloody. I was repetitive–stating the same things over and over.

I was admitted for a brain injury for a few days with a minor basilar skull fracture. To this day, I still don’t remember the days before the accident or about 10 days after. All I remember is vaguely seeing the grass and sky in my windshield as I rolled, loud metal noises, and screaming and pressing my horn into the hillside. Needless to say, I got a D that anatomy exam–it was bone and muscles and I had forgotten a week worth of material.

It seems like a lot, right? But not too much…? There was more…

I did ok for a few years. My grades got better. I was starting to see more As than Bs. I simultaneously loved and hated nursing school (much like everyone does).

In May 2013, I woke up to go to work at the hospital where I was a patient care technician. I had noticed my left hand and arm were numb. I figured I slept weird on it and ignored it–I was running late. I got to work 15 minutes later, noticing the numbness and tingling had spread quickly and intensely through my entire left side. I looked over to my care coordinator to ask if she had ever experienced anything like this. I opened my mouth to ask her and as I started to try to speak, I felt my entire left side of my face start to slide and go numb. The words coming out of my mouth weren’t making sense. I blinked and tried to ask again because she looked confused. I tried to lift my left hand up to touch my cheek and couldn’t move it. It all went black as I hit the floor… distantly, I heard the rapid response called overheard.

And then I opened my eyes and I was in the ER with a chaplain speaking to me. The stroke cart was being wheeled into the room. I knew the nurses from bringing patients in on the ambulance. The doctor was asking me questions about times and asking me to move things (why can’t I move that?). My manager was standing there on the phone with my husband (we had gotten married that year). They were talking to me about TPA.

I’m 23… what do you mean you think I’m having a stroke? Yeah lupus runs in my family… shit… my words sound jumbled… I’ll shake my head yes and no. There is my husband. Yes… birth control–I take that. No… don’t smoke. Yes–give the TPA. Yes–fine, fly me to that hospital.

It happened so fast… before I knew it, I was being loaded into a helicopter. I was in the air flying over my city. I was 80 miles away in another CT machine, getting more IV contrast. I was in an ICU bed. I wasn’t allowed to get up to pee. I could talk now though–that was a plus. My mom lives ten minutes away, at least I wouldn’t be alone but it would take my husband almost two hours to get to me if he drove the speed limit. I spent three days in the Neuro ICU while they ruled out causes and sent me home on medications. I was treated for a stroke but they determined that the cause wasn’t ischemic but rather related to more electrical/migraine activity. It was strange, I’ve never even had a headache. Who knew a migraine could be so scary?

It happened so fast… before I knew it, I was being loaded into a helicopter. I was in the air flying over my city. I was 80 miles away in another CT machine, getting more IV contrast. I was in an ICU bed. I wasn’t allowed to get up to pee. I could talk now though–that was a plus. My mom lives ten minutes away, at least I wouldn’t be alone but it would take my husband almost two hours to get to me if he drove the speed limit. I spent three days in the Neuro ICU while they ruled out causes and sent me home on medications. I was treated for a stroke but they determined that the cause wasn’t ischemic but rather related to more electrical/migraine activity. It was strange, I’ve never even had a headache. Who knew a migraine could be so scary?

I got better and spent the summer in Minnesota, leaving a few weeks later. It was between my Junior and Senior year so I had secured a spot in the Mayo Clinic externship program for 10 weeks on a trauma floor. I still had weird neurological symptoms all summer long but was still titrating off of medications for it. I tried to down play it and focus on what was to come.

I came home a bit smarter and ready to finish nursing school with a bang. I was beginning to look at jobs and apply for interviews, it was my goal to have an offer by January. I was spending my free time studying and applying. My grades were looking very good. I was the public relations officer for SNA and it seemed like everything was going my way.

Until my husband’s birthday. My husband came home to find me in full tonic clonic seizure activity on our kitchen floor. Never had I had a seizure until that day and in the span of a handful of hours, I had three separate events. I was admitted and started on an anti-epileptic medication. Over the course of the school year, I had multiple events resulting in admissions to the hospital and the intensive care unit, multiple titrations of medications, multiple visits to neurologists, multiple eegs. I thought this was going to be the year I had to drop out. My medications had me so unable to focus and I had missed so much class there was no hope to graduate. It was by sheer will and determination and the grace of my instructors to help me work around my diagnosis that I was able to pass that year.

So What Does This Have to Do With Anything? You Grow Through What You Go Through.

Resilience is how you come back in the face of adversity. When dealt a hand, how will you respond? It is easy to look at a person on Instagram or Facebook who projects a perfect picture and say “I will never be him or her… they’re perfect.” However, this discredits our own ability to achieve our goals way too much. The images we see only show partial truths.

The problem social media has is that we only see half the truth or none at all. We see what people want us to. We see perfectly choreographed pictures meant to endorse an idea. Often that idea is “I made it!” It is not always that people want YOU to feel inferior but that they want to feel better about their own lives, so they create their own narratives. They present their autobiographies in a more palatable way.

Me? Guilty. Guilty AF. Put me away, Judge.

However, now you know that behind the perfect picture is an imperfect person–and quite frankly, they are my favorite types of people. To get where I am, I had to constantly get thrown several steps backwards and then fight my way forwards every time. But every time I had to face adversity, it taught me how to problem solve and how to use my resources. As cliche as it may sound, what didn’t kill me made me stronger. It shaped my ability to be resilient.

What Does Resilience Do For You, Then?

So let’s talk about traits emotionally resilient people have and why nurses or pre-hospital folks or really anyone in medicine or emergency response can benefit from it.

- They practice good self-care.

- Part of dealing with other people’s crises is learning to be able to know when it is time to put that burden down and focus on yourself. Understanding that you are one person and can only save the world once your mind, body, and spirit are cared for is something many people never learn. As a result, they burn out or develop vices to deal with the ugliness of the world. They inflict more harm on themselves in an effort to stop the emotional hemorrhage.

- “Make it a priority to create a homeostasis (a baseline) for yourself–then take time to bring yourself back to that place. Care for yourself so you can care for others.”

- They understand bad things don’t define them.

- At any time, something can go wrong–whether it is simply because Mercury was in retrograde or because you over-estimated your own abilities or because you took a short-cut when you shouldn’t have. Regardless, a bad thing happened. Now what? Well… how do you move on? Do you continue to make the same mistake, allow the worse thing to continue to dictate the circumstances of your life or do you control the narrative? We cannot always control what happens but we can control what we do after the fact. Do we run and hide, pretend it isn’t happening, or do we face it, learn from it, and come out better? We are defined by how we REACT to the catalyst, not necessarily by the catalyst itself.

- “If it doesn’t matter in five years, don’t let it bother you for five minutes.”

- They treat others with compassion.

- Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. It is considered a more noble feeling than sympathy in that it puts two people on level playing ground as sympathy is defined more of feeling pity for someone. Some people feel this is a form of being looked down upon when you already feel low. People with emotional resilience understand what it is like to be low–thus they feel compassion. They do so in a manner without judgement–they understand what ugliness and hurt looks like. These are the people we serve as emergency responders and healthcare providers. We see humanity at its worst thus they need us to show humanity.

- “I see you because I was you…”

- They understand what it means to “race in the rain”.

- Life will never be perfect–the emotionally resilient have learned this. Things will go wrong. Train for the worst case scenario but hope for the best. Accept that things are in flux and are dynamic. Expect the unexpected and make the best of that. Emergency medicine and first responders are ideal examples of this concept.

- “…grant me the serenity

to accept the things I cannot change;

courage to change the things I can;

and wisdom to know the difference…” –Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971)

- They admit when they need help.

- Being first responders and healthcare providers, we are expected to be proficient in problem solving and critical thinking, swift on our feet, and courageous in the face of adversity. However, it is important we acknowledge our short-comings both in knowledge and in coping. We need to know to ask for help when lives depend on us, including those times when our own lives depend on our abilities to admit we need help. Every year, more and more first responders and healthcare providers succumb to the darkness of their jobs rather than admit their perceived weaknesses and every life extinguished is one too many.

- “From what I’ve seen, it isn’t so much the act of asking that paralyzes us–it’s what lies beneath: the fear of being vulnerable, the fear of rejection, the fear of looking needy or weak. The fear of being seen as a burdensome member of the community instead of a productive one. It points, fundamentally, to our separation from one another.” –Amanda Palmer

- They know when it is time to listen, when to be supportive, and when to allow for space.

- Having needed your own time to be heard when you speak, to feel like you were supported, and needed time to be alone in your thoughts, you understand that people need what they need when they need it. The emotionally resilient understand that to push too much against a rigid trunk may cause it to splinter and break where if left to its own devices, it may grow strong on its own. They understand that people cope with things differently and do not remain static in their processes.

- “The wounds that never heal can only be mourned alone.” –James Frey

- They build a tribe of supportive people.

- The resilient understand that people can drain your energy and impact your healing so they choose who they surround themselves with purposefully. They find people who support them and while those people may not necessarily understand the problems they see or experience, they still support their personal growth through it all.

- They know who they can go to for support and who will give them the truth they need versus the people who will simply perpetuate drama.

- Some of the most important things a person learns about themselves comes from the people they respect. Some times, we have inflated self-esteems or overly low opinions about ourselves so it is important we have people we can rely on to tell us how it is. Are our skills lackluster? Is our critical thinking off base? Do we put off bad airs around colleagues? Your person will make sure you’re not left in the dark. Meanwhile, avoiding people who will inflate your ego or trample your dreams will help you stay within your homeostasis.

- They possess an ability to reflect on themselves as they have developed self-awareness.

- This particular point took me a long time to develop. I had to learn to be honest with myself. If you read my post about my first year in flight (here) you’ll recall how I suffered from a bit of an ego coming from my ER but then an overly low sense of self-worth when I got to flight. But bringing myself back to center and being able to give honest evaluation of myself has been a constant struggle that has gotten a little easier all the time. Becoming more self-aware allows you to internally tune your chords to create a better running human and make you a better first responder/healthcare provider.

- They have an ability to be grateful.

- Life is full of disappointments–we often don’t get what we want no matter how hard we work. Whether it’s the flight job of our dreams, that paid firefighter job, the medical school admission we wanted… learning to be grateful for the opportunities we DO get (“I did get the interview at least…”) is another difficult lesson. Learning to see failure and rejection as lessons as opposed to the end of your dreams is step one to re-framing your thinking. The resilient understand not everything goes right the first time but they are grateful for what they already have and what they were offered. They get excited for what may come. It isn’t to say they can’t be disappointed, its just they don’t wallow in their miseries.

Becoming More Resilient

Becoming More Resilient

Short of having gone through some dark things and developed coping mechanisms, resilience can be learned. I’m not going to reinvent the wheel though–many great articles exist on the ability to re-frame your thinking to become more resilient. It all starts with how you critique your past and prepare for future challenges.

- Don’t allow yourself to be stuck in negative thought cycles.

- Stop being afraid to fail– you will never succeed if you never try!

- Do mothers and fathers criticize a baby for falling after taking a step? No… they celebrate that first step and when the baby finally walks, no one remembers the baby falling. So too when you succeed, no one will care about how many times it took you to get there.

- Find the lessons in past failures or challenges.

- What can you learn? Consider job interviews– every interview is a practice for the next one. Take what went well with you, get rid of what didn’t.

- Stop dwelling on your past failures and start planning for the next attempts.

- When the door shuts in your face, instead of staring at it…look down the street for the three more slightly ajar ones that may be alluding your gaze if you don’t look carefully enough–behind those doors may lie your path to your dreams.

- Emotionally distance yourself from the challenges you come across.

- Try to picture the situation you are in as if you were outside your own body, watching it play out. Would someone who was not you be upset about this? Try doing this exercise when you are distracted by crises to allow yourself an opportunity to evaluate your situation and options.

- “This too shall pass.”

- Things will move on–the passing of time eases the burdens of the soul. While it stings now, that broken bone will heal.

- Find the positives in the challenge.

- Attempt to reframe your mind–use a technique called positive reappraisal. It means that when you are in a situation where there is no real positive, you create your own. Consider you went to an interview that you did not get an offer for– you reframe the thought with “I at least got an interview–it means I am at least meeting standards needed to get into an interview. This is further than I was before.”

- Make it a point to get uncomfortable– stop staying in the shallows.

- A popular quote in the Crossfit community is “I’d rather choke on greatness than nibble on mediocrity”–and while I’m not into Crossfit, myself, I really like this quote. Mediocrity in this example is being comfortable but boring. Make it a goal to go against your comfort levels to attain the greatness you want, whatever greatness means to you.

Failure has such an ugly connotation associated with it. However, we shouldn’t allow what we perceive as failure to make us feel less awesome than we really are. Us failures are an awesome people–we survive and overcome. We are proficient in adapting and problem-solving. Failure is really actually quite beautiful. So whoever you are, wherever you are… if you’re out there looking at some Insta-celeb’s ‘Gram and thinking how your life doesn’t measure up, please pick your head up and straighten that crown. You are every bit as successful and amazing.

–Clear skies and tail winds.

Footnote: Obviously there was a lot of personal stuff I divulged here–I really hope my own personal story of perseverance has maybe inspired you to stay your course. Feel free to share your own stories of failure and overcoming in the comments to inspire your peers. As always, I welcome any and all feedback.

Patients will burn you despite you breaking your back for them. The pay will never equal the work some days. Lunches won’t come some days and your bladder will harden to that comparable to those weird frogs that hibernate for years in Australia (I pulled out that metaphor from somewhere…don’t @ me).

Patients will burn you despite you breaking your back for them. The pay will never equal the work some days. Lunches won’t come some days and your bladder will harden to that comparable to those weird frogs that hibernate for years in Australia (I pulled out that metaphor from somewhere…don’t @ me).

Becoming More Resilient

Becoming More Resilient