Any day now: they’re going to see me for the fraud I am.

Any day now: I’m going to hear the words “We made a mistake… We’re letting you go…”

Any day now: I’ll have to look the loved ones of a patient in the eye and admit “I simply wasn’t good enough… I never should have been here.”

Any day now: I’ll work up the nerve to turn in my flight suit and walk away.

Spoiler Alert: That day never came. I’m still here.

A Big Fish in a Decent Sized Pond (Maybe a lake depending on your definition)

I ran around the emergency department as the float nurse. It wasn’t looking like breaks were coming today but not much else was new. I stopped in this room to help another nurse settle her ambulance or that room to start an IV on a tough stick. It came easy. I knew my role. The department was changing, the merger with a large healthcare entity meant a lot of new policies, new flow patterns, new and (in my opinion) inferior equipment to learn, and with that, a great deal of migration of senior nurses out. We were learning how to become a trauma center, dealing with massive influxes of education and memos in our emails, and learning how to deal with trauma surgeons. The psychiatric patients, the overdoses, the high maintenance but low budget level-3 influxes, and the mix of serious and not serious flooding into the waiting room come 1100 with holes in the nurse staffing. “5 to 1 again guys… Steph, you have two social services holds–waiting for nursing home placement…”

Business as usual.

It was my normal. I felt that after three plus years in the emergency department, I could handle 95-99% of what walked through that door and whatever new hoop the management overlords threw at us next. It was chaos, madness, insanity, insert whatever synonyms you want for “batshit freaking crazy”–but it was home. This was my niche. I knew my protocols, could almost call a diagnosis through chief complaint and physical assessment alone. My husband was accustomed to the phone call an hour before shift change with the “heeeeeeeeeyyyyyyy…”. He knew on that first word I’d be staying late again.

I was one of the people my peers called for hard sticks. My younger staff knew they could comfortably ask me things without me judging them. Many today still remember that when they say, “I want to be like you, someday”, my response would be “No… do more, be better.” I had been asked to precept nursing students, paramedic students, and new hires. I was asked to be on committees. I was nominated for awards. My frequent flyers knew me and asked for me. It was hard not to be egotistical but I had hit my stride. For as frustrating as the emergency department can be, it was where I shined.

In my personal life, I always had a low self-esteem but in my professional life, I was peaked in my mind. I found my flaws and I smashed them to come out better. I felt confident.

It wasn’t always like that though. It took months to years of being frustrated, being angry, being hopeless, and occasionally melting down in the med room.

Loving the ER Nurse Life

Precepting a Nursing Student

That First Year in the ED

I came to the ED from a small community hospital ICU. The kind that could handle respiratory failures on ventilators and DKA on insulin drips. We had a cardiac catheterization program and I’d see a-lines on occasion. I was trained in balloon pumps but never actually saw them. I had a little less than a year in when I made the move to the ED. The ED was where I always wanted to be. I was shot down in nursing school which was devastating so I was elated that the opportunity came.

I was blessed with two of the best preceptors. They were thorough, well adjusted, confident. I couldn’t wait to be “them.” I trained exclusively on day shift but was hired for night shift. My first time working nights was my first day off of orientation. I went in happy and excited and within a few hours I ended up crying in the med room. Night shift staff was tough but not cold or mean… They had the mentality that they had seen some shit and you needed to harden up to survive. That lesson took me a while to learn.

That whole first year was a roller coaster as I learned the ropes of night shift. It was making more out of less. Team work was key to survival. It was learning that while it’s ok to be “nice” recognizing there is ugly in some patients and they will mow you down. I was nicknamed “Suzy Sunshine” and my techniques for handling psych patients were sometimes met with skepticism. I got hurt a few times by patients because I gave them the benefit of the doubt and left them have too much rope.

It got better though. Every shift I learned new things. My skills improved. My report with patients stabilized to a compassionate but professional manner. My confidence grew until I no longer questioned my place–I earned it.

Now, I’m sure by now, you’re wondering– Steph… I don’t really particularly care about your ER days. When are we getting to the flight stuff?

Because this first year for me started off excited for the new adventure but quickly the romance dissolved into terror when I started to question my abilities to fulfill my role. And over time, with a good support system and mental fortitude, I built myself to a place of professional confidence. And this entire dynamic reared its ugly head again during my first year in flight nurse.

Presenting at a Trauma Symposium

Last Day in the ED

There is a Science Behind The Emotions

Transition shock. The term couldn’t be better named. It is often used to describe the negative array of feelings new graduate nurses feel when they first transition into the role of the professional nurse. Common themes that emerge are the fear of “being exposed as clinically incompetent”, failing to meet the needs of patients and hurting them as a result, and not being able to bear the responsibilities their new role entails (Boychuk Duchscher, 2009). This particular conceptual framework has been identified as a major reason new nurses switch specialities or leave nursing bedside within their first year. It is a pervasive albeit insidious secret in nursing, one they do not prepare you for in school.

But beyond the transition shock, there is also another identified concept that has relevance in my first year and that is the impostor phenomenon. It derives from the field psychology and was first really studied in the 1970’s and 1980’s. It is the “psychological experience of intellectual and professional fraudulence…” during which individuals experience a fear that their peers possess perceptions and beliefs in their abilities that may be inflated and as a result, the affected worry that they will be identified as a fraud (Mak, Kleitman, and Abbott, 2019). The concern derives from the idea that should the person fail to replicate performance to the standards ascribed to them, that they will be ousted as fraudulent. This phobia remains despite praise or achievement and they usually discount their own abilities as “luck” or “right place-right time”.

Related to this framework is the idea of perceived fraudulence. While it is similar to the impostor phenomenon, it focuses more on the idea that individuals are concerned with “impression management”and are pre-occupied with the idea of managing their self-worth and social image. These individuals are usually unable to overcome their own intense self-criticism and as a result, when placed in new environments, will constantly monitor for social cueing from their colleagues for fear of “being discovered.” At its heart, they fail to realize that their own high-expectations often do not translate to those of others and as a result, they constantly “front” themselves to protect their image.

Psychology Today did a short and sweet write-up on the topic. And as I read these paragraphs back to my husband, he sort of just nodded…

It boils down to a sheer lack of confidence in one’s self not the lack of ability. This was a lesson that took me a while to learn. I was surrounded with the best and the brightest. I felt like that person who managed to sneak in the back of a major event, uninvited and constantly shifting my eyes waiting for the bouncer to throw me out on my ass. It is exhausting. Truly. Being in flight, where we are expected to be the best and operate at high levels of precision is certainly something but I was thrown right back to year one in my nursing career. I didn’t think I was hot enough shit for this role and someone soon would see right through me.

And they kind of did. Actually, just one. And he made all the difference in my attitudes.

Taking the Big Fish Out of the Pond and Tossing Her Into An Ocean

Honestly, I never really saw myself as having a confidence problem. I always felt pretty secure in my abilities. As previously stated, I was a rising star in my ER job. I had just finished my masters degree two months before starting and I was still riding that high. As usual, I came into my new job with the same confidence I had for my old job. Until I started to realize the gravity and immensity of what I had began. It was a swift kick in the ass to realize how little I actually knew. I knew who to ask for help to and what my resources were but the immenseness of “not knowing what you don’t know” was the crux of my existence. Not knowing what I didn’t know yet was this constant plague to me as I played out every worst case scenario in my head.

And like any good little worker, I faked it until I made it. But the mistake I made was coming off as arrogant or overcompensating. I was eager to learn and improve but too scared to be seen failing. I fell victim of the impostor phenomenon. In my attempts to negate my own feelings of inadequacy, I often postured and tried to seem more confident and competent than I was. I was textbook perceived fraudulence in living color.

But my base manager saw straight through my front. He called my bullshit right out. It hurt to hear. It is a weird feeling to have someone you respect and look up to call you out on having no confidence or a low self-esteem when all this time you had convinced yourself that you didn’t. I was in complete 100% denial of my situation. And it took someone saying, “relax…” and basically laying out how your actions can be perceived as abrasive to others. I just thought I was protecting my own image but in reality, I was pushing others away. It was a lonely feeling. Luckily, I had the support of people in my program to uplift me while I fumbled through figuring it all out.

And for that, I am ever grateful. If you take nothing out of this long-winded and emotional retrospective its this: find your tribe. Identify the people vested in your success. You will encounter people who hold their breaths waiting for you to fail–make them suffocate. For me, it was my preceptors and partners. It was that one base manager. Multiple flight paramedic preceptors from a variety of bases in my agency. My director. I found people who believed in me.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Because here is the secret: if you didn’t belong here, you would not be here and if you by some chance DID weasel in, you would’ve been screened out early.

It was that realization and constant cognitive framing that I survived myself. That was ultimately my biggest hurdle: getting over my damn self. It wasn’t learning protocols: thats read and regurgitating algorithms. It wasn’t learning to work around a running helicopter: that takes practice. It wasn’t learning how to deal with the myriad of different situations I’d find myself in: that takes teamwork and experience.

No, the biggest hurdles in learning to be a flight nurse were:

- Developing a sense that I earned my place and I did belong here.

- Recognizing it was going to be hard and I would indeed have times I fail.

- Every time I fail is an opportunity for growth.

- Learning to trust myself again–I knew enough to go back to the basics every time and all good medicine stems out from good foundation of the basics.

But what about the actual details of that first year?

By now, if you’ve read this far, you’re probably sitting there pondering what you got yourself into. How in the world does this pertain to preparing me for my own first year?

Every program is different so my actual orientation will be different than yours. I can go on to say “I spent 24 hours on CVICU to see open hearts, balloon pumps, drips, and ECMO… 24 hours in NICU to see how newborns are handled… 24 hours in the PICU… so long on an active 911 ambulance…” And really that was my first month. It was bouncing around different units for exposure. But we’re healthcare providers, we know we have to be dynamic and gain exposure to all these things.

The career ender and soul killer through all of this is your swagger. It is the balancing act of being arrogant and being scared of yourself because your confidence has not yet found the happy medium. Studies have shown that 1st year can make or break people and in new graduate nurses, many will leave their specialty to another specialty or bedside all together if they don’t feel confidence begin to grow.

Accepting Help and Admitting Weakness

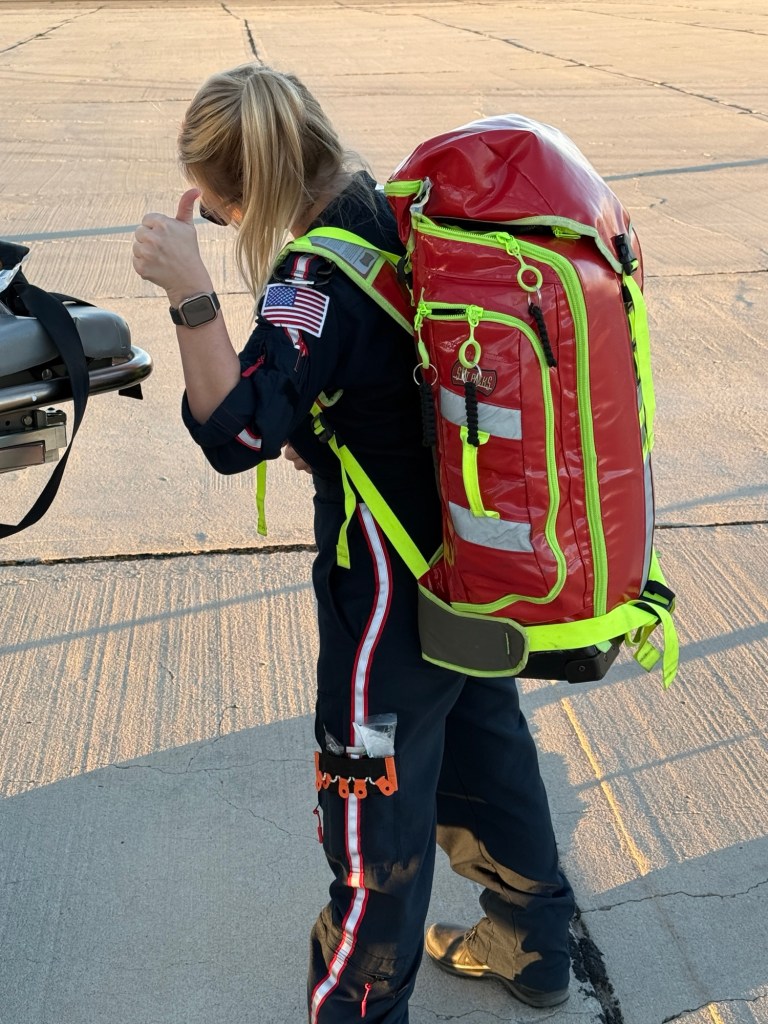

My first time flying in the helicopter

Through this entire post, I kept deleting things and rethinking what I wanted to talk about. I kept thinking that admitting my short-comings and admitting I struggled with confidence would undermine my credibility. We in flight are expected to be the best but here I am admitting I questioned myself. I realized that I still fall victim to the conundrums I previously discussed–admitting my struggles may undermine my image. Gone is the badass albeit tiny flight nurse as the silly goose rears her head. At least that is what I thought. Half of the battle was recognizing the negative self-talk and beginning to take stock in my strengths and weaknesses without belittling myself.

That being said: its ok to admit you’re not all that and a bag of chips (I mean you may still be a bag of chips but like the store brand not the flavorful kettle cooked ones). Admit you don’t feel comfortable with things yet and ask for help. Ask for additional training. You’ll be more respected for identifying these things yourself than if you try to tread water and hope people don’t think you’re incompetent.

I say it because I know it…

The huge blow in my first year came when my orientation period was extended. It was following the heels of a night flight to the middle of nowhere. She had fallen down too many stairs after imbibing and met trauma center criteria but by ground it would take too long. So in we came on our white horse (or in this case a blue and white EC-145). It was what should have been one of my last orientation shifts and by then, I should’ve been running the call. I hadn’t had a great deal of scene flight experience and my preceptors generally had different approaches to these patients. One of my partners was supposed to sit back and watch or be directed by me. But in the end, I ended up getting disorganized and essentially did not perform as a provider partner was expected to off of orientation.

So two weeks my orientation was extended and my end of orientation simulation was cancelled. It was so disheartening. I was mandated to shifts on a local ALS ambulance where I was supposed to work on my field skills. However, I kept getting BLS transfers or nursing home transport runs instead of what I needed. I was so frustrated. But then came the final shift with a big trauma– MVA, pregnant patient, ejection, middle of winter, the gamut. I performed well enough as a partner to qualify to challenge my simulation. I was able to pass that and come off of orientation.

But when I thought that I was done growing, it was really only the beginning. I had new patients, new pathologies, new flights where I constantly felt challenged. But every month that passed, I felt a little more confident. It was like the ER all over again, I felt myself settling in. I recognized I had places to grow but when I looked back to where I had come from, it was like I was a whole new flight nurse.

Some of the Little Things They Don’t Prep You For

- The amount of classes you have to take, the amount of training you undergo.

- Learning to deal with boredom–in between the calls when the required trainings and base chores and responsibilities of your job are done there is a lot of down time. Learning to keep yourself busy is a hard thing. (My response was to start a blog)

- And in that inactivity, how to stay healthy. Learning to eat right or keep up being active.

- The dynamics of working with people, especially the grizzled veterans of flight. You get some salty people, don’t let em diminish your shine.

- Learning how to dress for the heat of ICU’s but the cold of a scene flight in the middle of a corn field in single digit weather (because “seasons”).

- And this one is for the ladies, how to deal with inundation of Facebook friend requests from firefighters you meet on the job… yeah, I said it.

That first year of flight will remind you of that first year of nursing. You’re going to see up and down and sometimes a steady “in the middle.” But be resilient in the face of bad times and accept your praise/accomplishments. Recognize what you feel is not uncommon but do learn how to overcome it. The first year is exciting and scary but you can survive it! Just stay the damn course!

-Clear skies and tail winds!

Do you have any advice for other aspiring flight nurses or novice flight nurses? Leave a comment with some tips and tricks! Got questions I didn’t answer? Feel free to slap those babies in the comments too!

Make sure to subscribe for new posts!

Patients will burn you despite you breaking your back for them. The pay will never equal the work some days. Lunches won’t come some days and your bladder will harden to that comparable to those weird frogs that hibernate for years in Australia (I pulled out that metaphor from somewhere…don’t @ me).

Patients will burn you despite you breaking your back for them. The pay will never equal the work some days. Lunches won’t come some days and your bladder will harden to that comparable to those weird frogs that hibernate for years in Australia (I pulled out that metaphor from somewhere…don’t @ me).