By someone who’s been doing this long enough to know better

Let’s set the scene: you’ve got three years in critical care under your belt. Maybe you’re a paramedic who can RSI in your sleep or an ICU nurse who can titrate five drips with one hand while eating cold pizza with the other. You’ve memorized the CAMTS requirements, passed your CFRN (maybe), and your Google search history is full of things like “how to not puke in a helicopter.

You’re ready to fly, right?

Well… slow your rotor wash, baby nurse.

Three years of experience is no joke. That’s a solid foundation. But it doesn’t mean you’re fully baked yet. And in flight medicine, undercooked can get spicy real fast. There’s a reason why a lot of flight teams quietly prefer five or more years, even if the brochure says three. That extra time matters, and it’s not just because we’re gatekeeping the cool jackets.

Let’s Talk About the Unicorn Myth

You know the one. The myth that once you hit three years, you’re ready to slap on a flight suit and start saving lives from 2,000 feet in the air like a stethoscope-wielding superhero.

But flight nursing isn’t just ICU or EMS in the sky. It’s ICU plus ER plus trauma bay, plus resource nurse, social worker, and tech support—sometimes all at once—while flying through turbulence and listening to your pilot talk about wind vectors like it’s a normal Tuesday.

The Research Is In, Y’all

According to a 2022 CFRN Pulse Survey, over 35% of flight nurses have more than 10 years of experience. That’s not by accident. Those extra years mean more reps with sick patients, more bad calls under your belt, more creative cursing during equipment failures, and most importantly, better judgment when things go sideways mid-flight (which they do).

A study in PMC also found that more experienced nurses tend to have higher “compassion satisfaction.” Translation? They’re less likely to lose it when their vent fails, their partner is stress-eating almonds, and their patient’s BP is circling the drain at 2,500 feet.

Now Enter: Maturity

I know, I know…nobody likes being told “you just need to be a little older.” But here’s the deal: age equals perspective. And flight nursing requires the kind of emotional intelligence that only comes from years of experience and probably a few existential crises. You need to be the calmest one in the aircraft while your partner’s troubleshooting a dying IV, your pilot’s yelling about airspace restrictions, and your patient is suddenly bleeding again from a place you already bandaged.

Let’s be honest, maturity also helps you not panic when your patient is crashing and your monitor screen goes dark, and the only thing you hear is the faint beep of your own stress response.

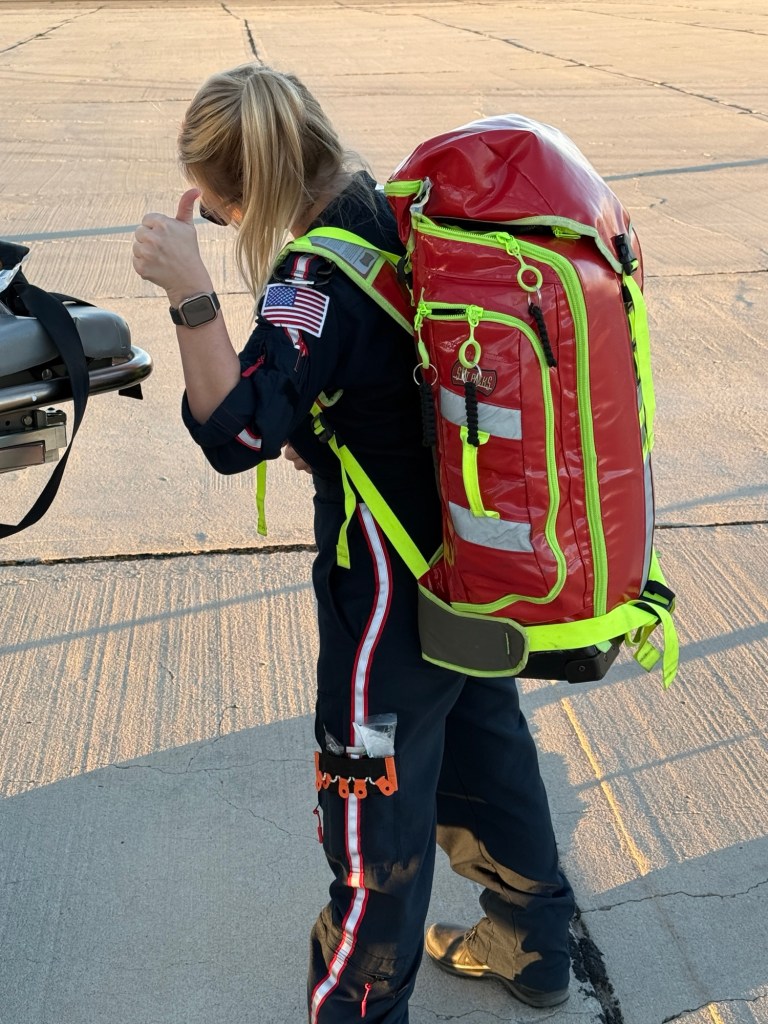

Personal Growth: A Seven-Year Transformation

I started this journey at 28, full of energy and ambition. Now, seven years later, I look back and barely recognize that version of myself. The experiences, challenges, and yes, even the mistakes, have shaped me into a completely different nurse and person. It’s not just about accumulating years—it’s about the growth that comes with them.

Interestingly, research backs this up. Developmental psychology studies suggest that people often experience significant shifts in perspective, emotional regulation, and decision-making every five to seven years. In a high-stakes environment like flight medicine, those changes can be the difference between reacting and responding.

Bottom Line: It’s Not About “More Time to Wait.” It’s About More Time to Prepare.

Three years will get your foot in the door. But taking a little more time—whether that means another couple years in the unit, more variety in your calls, or just letting your prefrontal cortex finish cooking—isn’t a punishment. It’s a favor to future you. The one who’ll be flying at night in winter with a hypotensive trauma patient, a rookie pilot, and a med bag that’s somehow missing the Doppler.

If you’re at year three and ready to go? Hell yes. Chase the dream. But go in with your eyes wide open and your ego checked. Because this job doesn’t just demand skill. It demands grit, grace under pressure, and a little seasoning.

And if you’re already flying with “just” three years under your belt? That’s okay too. Just know it’s not about having enough time. It’s about making that time count.

And hey—at least now you know to bring your own snacks. Nobody tells you that part in orientation. Or what to wear under your flight suit. Or that you better figure out your hydration strategy, because once you’re in the aircraft, you’re not peeing until you’re back on the ground.

(Flight nursing: where your bladder learns discipline right alongside your brain.)

-Clear Skies and Tail Winds